by Lindsey Welch

One topic that frequently comes to mind when discussing images in our contemporary times, is the vast accumulation of photographic, auditory and video based media being released into the internet-ether that we are all connected to.

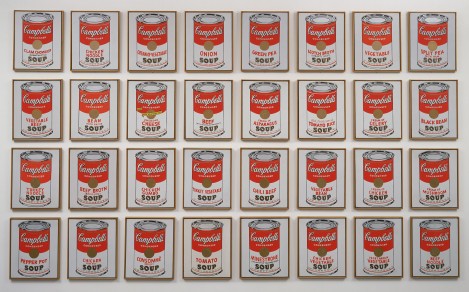

32 Campbell's Soup Cans 1962 - Andy Warhol

Appropriation in art has been a hot topic, probably even as long as there has been art. Most commonly, appropriation took from famous works, or well known pop-culture icons in order to spark commentary and discourse on subjects such as originality and authorship, as well as social commentary and engagement [1]. Sherrie Levine appropriated from famous male artists such Walker Evans in order to critique the ideology surrounding the limited roles of females in contemporary art history [2]. Even more well known, Andy Wahol and his repurposing use of already established and recognizable brands, logos and pop-culture images. Possibly, one of his aims was to criticize the presence and repetition of such things and its affect on popular culture [3]. Currently, Richard Prince and Barbara Kruger’s work appropriated imagery acquired across the internet and popular media stands out in both their capacity to open dialog as well as controversy. In 1977, an exhibition titled Pictures, noted the growing extent to which our lives are governed by the media’s imagery [4].

After Walker Evans 1981 - Sherry Levine

Examples such as these acknowledge media inundation and its affect or evidence in our culture and ideology. Though Appropriation Art hit mainstream recognition with modernism gaining to the forefront in the mid-20th century, following rampant consumerism and mass media, it was not until wide spread use of the internet and online media did art appropriation take an interesting new turn [5]. As noted above, there are famous controversial examples, but there are some lesser known works that open our eyes to image automation, our contribution to a coalescing mass of similar imagery, and even in collections of internet released tidbits that when evaluated together create a sometimes unsettling bigger picture.

Photographer and artist Michael Wolfe has amassed a huge collection of targeted and curated Google Street View imagery through use of the camera movement feature that he both acquired and discovered on his own through combing the application [6]. In one project, titled A Series of Unfortunate Events, he has presented a collection of random, often funny, accidents and occurrences caught through the automated imagining process of Street View capture. In another project, titled Interface, he has used the Street View controls to strategically align and place the user interface over areas of found Views thereby creating new art from automated media materials [7].

A Series of Unfortunate Events, #38 - Michael Wolfe

Interface, #28 - Michael Wolfe

Wolfe views this use of Google as a way to comment on the ‘dismantling of time and space’ as enabled by the application. It interprets contemporary issues such as automation, privacy, and events without context.

Corinne Vionnet appropriates travel images from publically accessible collections on the internet, then combines them to reveal a truth about a place’s collective memory. These ‘photo souvenirs’ when combined speak to a unified experience fueled by both the need to have interacted in a preordained manner as laid out by those before, and to have participated in what already exists [8]. In her series, Photo Opportunities, she examines the mass of similar snapshot from infinite sources that speak to both mass tourism and mass media’s direction of experience [9].

Photo Opportunities - Corinne Vionnet

The artist Emilio Vavarella, in his 2017 project Do You Like Cyber?, created an installation art piece based on messages acquired from the 2015 famous site hack, and following data dump, of AshleyMadison.com [10]. Within the data dump was a large collection of audio messages used by bots on the dating site, that Vavarella procured and strung together in this installation on parametric speakers that create a fragmented symphony of conversation which bounces around the room.

“These bots were programmed to engage the website’s users in online chats, getting them to subscribe to the website’s services. Despite the fact that the bots were designed to only contact males, they didn’t always function as they should have. This work focuses on a series of insubordinate bots that, in a post-anthropocentric fashion, displayed anarchic and unpredictable behaviors, such as chatting with each other for no apparent reason or contacting female users even if they weren’t programmed to do so. Do you like Cyber? puts the autonomy and interaction between artificial entities at its center, while leaving humans only partially aware of their presence.” [11].

Do You Like Cyber? Installation - Emilio Vavarella

A recording of the installation, which can be found on Vimeo [12], is a sampling of the actual work. The sound is unsettling and eerie, and speaks both to the seedy side of the internet and the existential question of a future connected by or with bots in our mass media-driven world.

As can be seen, this is a fascinating occurrence to accompany our vast sea of media floating about in the World Wide Web. Appropriation, in this sense, allows art to be created from the raw materials that are the flotsam of automation, social media, and anonymity that the internet affords. Now, more than ever, appropriation in art, and from the media stream, can help us to become aware of both the accumulation of and about, media’s unrelenting presence in our society; the questions it poses, and what it means to our future as artists and creators. Through the acquisition of these materials, these artists have been able to shed light onto both how our habits are directed by our immersion in this environment, and how when appropriately applied, it can guide us towards new understanding of its role in contemporary art creation.

[1]. Tate Modern: Appropriation < http://www.tate.org.uk/learn/online-resources/glossary/a/appropriation >

[2]. The Met: Sherry Levine, After Walker Evans: 4. < http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/267214 >

[3]. Phaidon. The fascinating story behind Andy Warhol’s soup cans. < http://www.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2013/february/22/the-fascinating-story-behind-andy-warhols-soup-cans/ >

[4]. Rowe, Hayley A. Appropriation in Contemporary Art. Inquires Journal. Nov. 2011. < http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/546/appropriation-in-contemporary-art >

[5]. MoMA Learning. Pop Art, Appropriation. < https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/pop-art/appropriation >

[6]. Brook, Pete. Aug 2011. Google’s Mapping Tools Spawn New Breed of Art Projects. Wired. < https://www.wired.com/2011/08/google-street-view/ >

[7]. Wolfe, Michael. Homepage. < http://photomichaelwolf.com/# >

[8]. Smithson, Aline. Oct 2009. Corinne Vionnet, Lenscratch. < http://lenscratch.com/2009/10/corinne-vionnet/ >

[9]. Vionnet, Corrine. Photo Opportunities, Homepage. < http://www.corinnevionnet.com/-photo-opportunities.html >

[10]. Zetter, Kim. Hackers finally post stolen Ashley Madison Data. Aug 2015. < https://www.wired.com/2015/08/happened-hackers-posted-stolen-ashley-madison-data/ >

[11]. Vavarella, Emilio. Do You Like Cyber?, Homepage. < http://emiliovavarella.com/cyber/ >

[12]. Vavarella, Emillio, Do You Like Cyber? Vemeo. < https://vimeo.com/200891249 >