by Brian Edwards

Hang me in the Tulsa County stars

Hang me in the Tulsa County stars

Meet me where I land if I slip and fall too far

Hang me in the Tulsa County stars

- John Moreland, Hang Me in the Tulsa County Stars

Uncertainty is the essential, inevitable and all-pervasive companion to your desire to make art. And tolerance for uncertainty is the prerequisite to succeeding.

- David Bayles and Ted Orland, Art and Fear

I probably owe the book Art and Fear another reading. [1] This will be third time around, but I am still drawn to it, especially when I find myself needing to touch base with myself, and what better way to do it than with book in hand. Art and Fear holds many wonderful lessons for aspiring and established artists. I especially appreciate his relating the experience of the ceramics instructor that divided the class into two groups, the first would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, the second on the quality of their work. It turned out that the quantity group produced the work with the highest quality:

It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work – and learning from their mistakes – the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay. [1, page 29]

My take on this story is that by starting, failing, and starting again only to fail again, the students were engaging in the very necessary process of experimenting and, more importantly, taking risks – making a decision to proceed ahead with only a notion of an outcome instead of a certain one, and being willing to do this again and again. Farmers know the story well – spring plantings occur well ahead of weather, actual crop yields, and prices at market.

Risk is by itself an interesting phenomenon. We’re all discouraged from taking all sorts of risks, from financial to health to personal and professional risks, and risk is an important topic in numerous academic disciplines ranging from economics to behavioral psychology. Many of us display attitudes towards risk that often baffle experts in risk assessment (cigarette smokers who are afraid to fly) and the failure of investors to understand the riskiness of credit default swap instruments contributed to the financial crisis of 2008.

But art doesn’t always imitate life and in the case of art making, risk can be a good and productive element of artistic growth. When I find myself returning to Bayles and Orland, it is always their section on uncertainty I await rereading that fortunately is not too far into the book. [1, 19] The authors relate many examples of artists going through many revisions before emerging with something worthwhile.

William Kennedy gamely admitted that he re-wrote his own novel Legs eight times, and that “seven times it came out no good. Six times it was especially no good. The seventh time out it was pretty good, though it was way too long. My son was six years old by then and so was my novel and they were both about the same height.”

My own process is largely experimental, and often repetitive. Even when I am in the midst of creating a series of images that are supposed to be connected thematically, I think about weather, time of day, and direction and possible quality of light as much as I do about place. In earlier days, I usually shot in spite of bad light; now I seldom do, even if a particular subject is on a bucket list of subjects that might fit in well with one or more series in which I am currently involved. Moreover, many shots that I have liked were surprises; found subjects rather than subjects known a priori. Others had to be reshot on different occasions until my own evolving vision of what I was looking for converged with the image I had just created. In this context, risk and uncertainty are not problematic, nor is realizing that control is often illusory.

Back in 2007, I drove through the town of Regina, which is in the northwest part of New Mexico, just north of La Jara and Cuba and a bit south of the Jicarilla Apache Nation Reservation. It was late in the afternoon and the lighting was in front of me, so I didn’t spend much time there. The shot below is one of nine I took that afternoon. This image was taken before I discovered the advantages of tilt-shift lenses, so in addition to the lousy light, there is way too much foreground and too little sky. At least the vertical lines are reasonably vertical.

Gas Station, Regina, New Mexico, June 9, 2007.

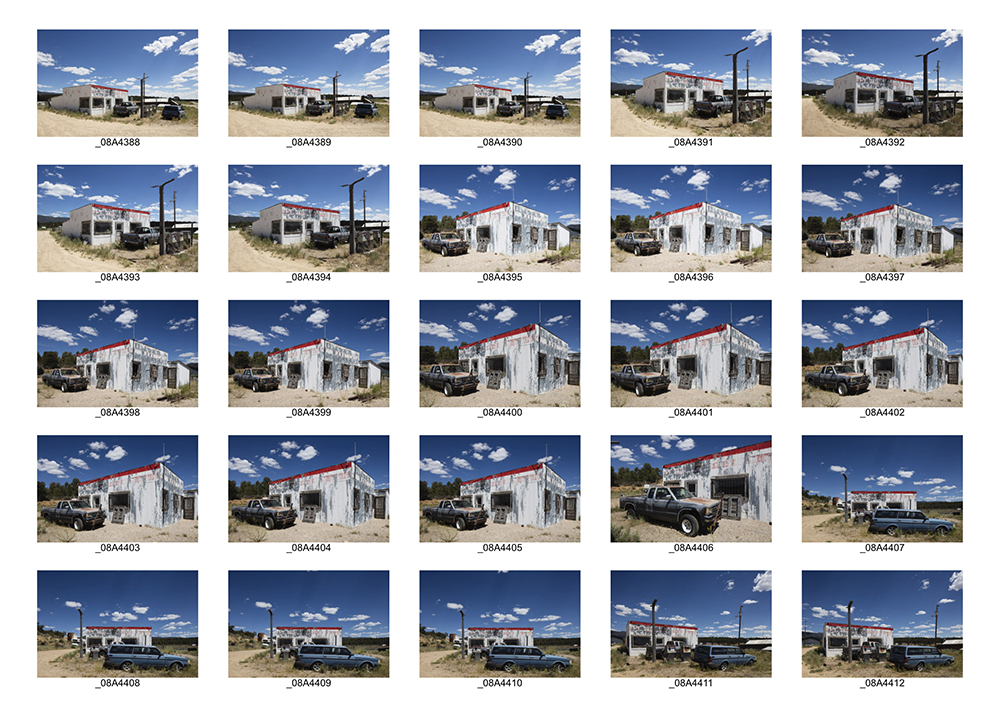

I returned to Regina during the summer of 2016 and took the following series of the same gas station. The much better light was a factor in making me more enthusiastic about taking the space a little more seriously, I was also more willing to explore the space more thoroughly and conduct my own impromptu experiment. What might this place yield in terms of an image or two that might be interesting enough to either include in a series or treat as a stand-alone singular image?

Gas Station, Regina, New Mexico, July 16, 2016

There are multiple images from this set that I think work pretty well, but I decided to choose the following for illustration (last image from the third row).

Gas Station, Regina, New Mexico, July 16, 2016

The truck and better light certainly help to make for a more interesting shot, but I also kept this particular spot in mind over the years since I took the original shot. I wanted to return many times, but coming to this spot at this particular time was accidental; it was a small part of a longer road trip that just happened to bear fruit the second time around. In any case, I do hope this example helps to illustrate the point made by Bayles and Orland, namely:

In making art you need to give yourself room to respond authentically, both to your subject matter and to your materials. Art happens between you and something — a subject, an idea, a technique — and both you and that something need to be free to move...E.M. Forster recalled that when he began writing A Passage to India he knew that the Malabar Caves would play a central role in the novel, that something important would surely happen there — it’s just that he wasn’t sure what it would be. [1, page 20]

I take license in interpreting Bayles’ and Orland’s definition of materials broadly enough to include the light and other conditions we find ourselves in when shooting. Nevertheless, risk can come in many forms in the context of making photographs. Not knowing what you are going to see or what sorts of conditions one will face upon arriving at a particular spot is but one risk. How often have I ended up driving through beautiful light only to arrive at my intended location when that light had passed, or when it was just too late in the afternoon to shoot, or it was raining? Other risks include how others might react to your work, or work you do that falls outside what you typically do, or outside of what others have come to think of what you do. I push ahead and make another vase, knowing ultimately that I have to be the judge of my own work and in whatever directions that work goes. Maybe my desire to read Art and Fear again is for the reassurance that taking risks can be disquieting and disappointing, but nevertheless worth taking, despite the risks.

Sources:

[1] David Bayles and Ted Orland, Art and Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, Image Continuum Press, 2001.

[2] John Moreland, Hang Me in the Tulsa County Stars, from the album High on Tulsa Heat, Old Omens, 2015.