by Brian Kyle

Sketching plays a very important, and almost integral role in my fine art photography. Before we find ourselves at odds I would like to make a few things clear, this is a technique that works well for me and my style of photography, but is obviously not going to be an option or an advantage for all photographers. I would however, recommend that you at least give it a try as conceptual exercise. In this post, I’ll briefly walk you through one of my photographs from sketch to completion. I’ve intentionally chosen a simple image because I think it will illustrate how even with a simple photograph the sketch still strengthens my concept, and how this pre-visualization exercise informs my approach to pre-production and production.

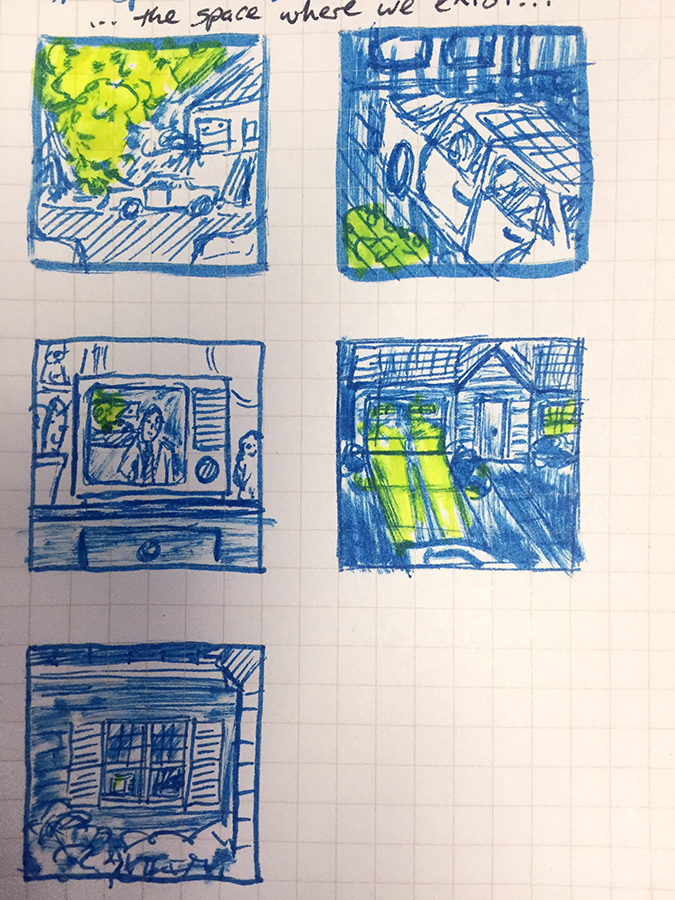

Early Concept Sketches for ‘Murmurations’, 2015

When I begin a new series there is always a lot of time spent with pen and paper (and napkins too) jotting down ideas potentially worthy of becoming a series of images. These ideas often consist of just a few descriptive words scrawled in my sketchbook, such as, “Taxidermy Animals (that look alive)”, “Portraits Inspired by Rene Magritte’s Son of Man (Symbolism!)” or “Cats in Hats”. Some of these ideas that get written down might be good, a lot of these ideas are probably pretty bad. The funny thing though is it often takes writing these ideas down to come to these decisive conclusions, an idea like, “Cats in Hats” might have sounded amazing in my head, but as soon as I saw it written down I realized that it wasn’t right for me. It might be fun to think about a project like that, but I wasn’t hoping to make a cute calendar, and I don’t even own a cat or know anything about what it would be like working with them [Full disclosure: This is not an idea I’ve ever entertained, just a fun example for this post].

Once I have a few ideas that I am starting to like I start some tiny loose sketches that help me visualize what these ideas may look like, or what components they might need to be successful. These images often are loose enough that I like to compare them to a doctor’s handwriting, the author can “read” them, but often no one else can.

For instance, the image above shows a set of early sketches that are exploring the idea of a set of images that are more related than they might first appear and each is revealed as the camera pulls backwards from the scene…Counter-clockwise from top-left: 1. an image of a car with smoke pouring from the hood. 2. that same car photographed from a different angle appearing as a news item in the small box next to a newscaster on a television broadcast, shown on a tv inside someone’s livingroom. 3. The TV is seen through the window from outside of the house. 4. The headlights of a car approaching the driveway of the house. 5. A closer view of the car that reveals the driver of the car.

I’m sure when you first viewed those sketches you couldn’t make out the idea I was exploring, but I could, and this is what makes this process so important to me. I don’t have to spend long working out an idea because the drawings don’t have to be good, but while I am sketching my mind is working hard on the idea. I have to be actively imagining what appears in the photos, what those things might looks like, I considering possible compositions and what lighting and color may look like, what the real important elements might be, etc. By making crude sketches I’ve forced myself to carefully consider and map elements of my idea that probably started as a poorly considered written prompt, such as, “background of one image connects with another”.

After I’ve engaged in the task of thumbnailing my ideas, I often find that my ideas weren’t solid enough to move forward. However on the rare occasion that I have an idea that I am still excited about, like the example above. I’ll often start working out more detailed sketches for individual photographs that I am hoping to make.

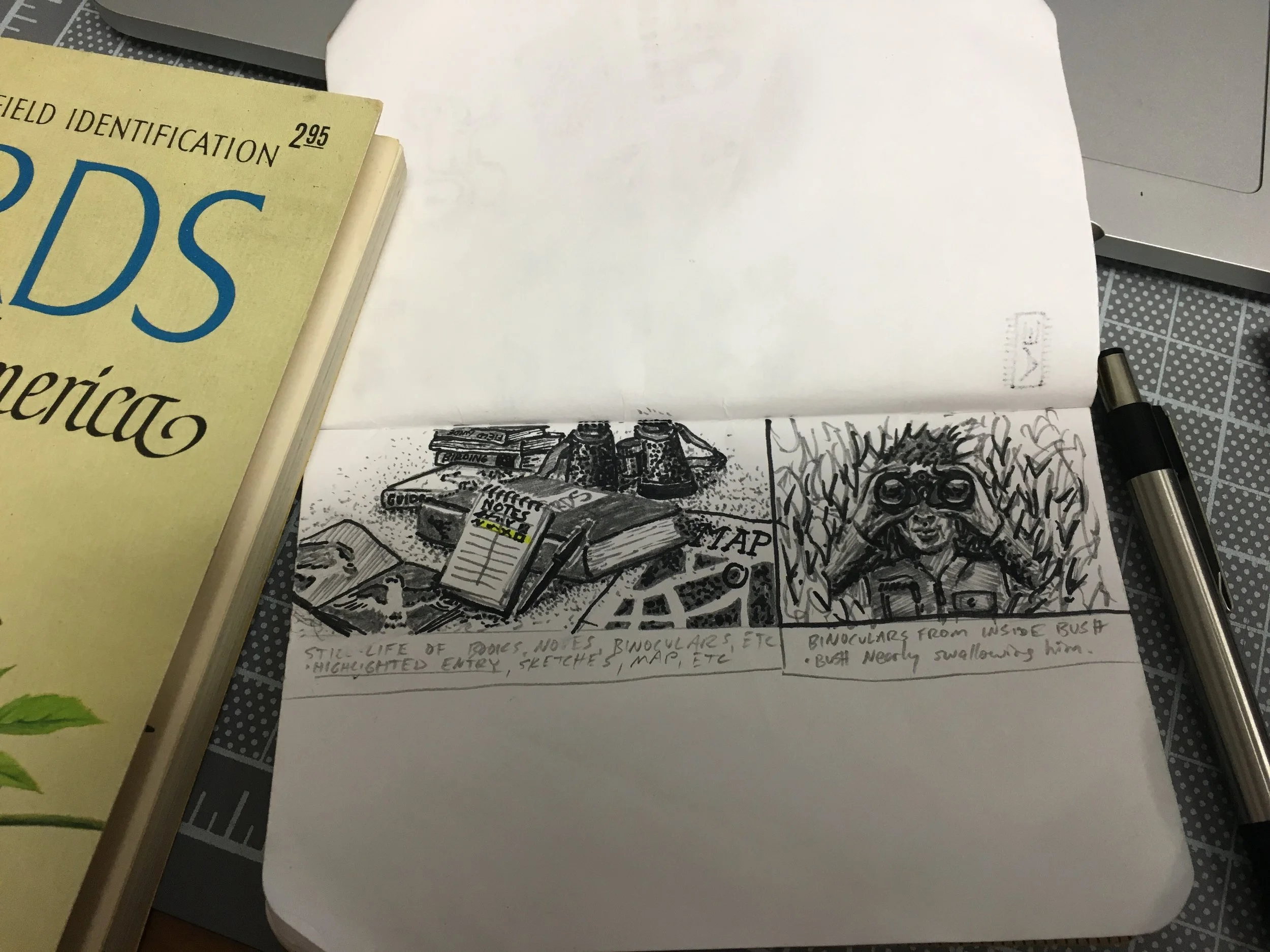

Concept Sketches for ‘Murmurations’, 2015

Unlike the thumbnailing process, as I make sketches at this next stage I am vetting ideas about composition, subject, and location. If I am working on a series, I don’t start photographing until I have multiple sketches that are prospects for photographs in the series. Multiple sketches allows me some early insight into the success of the series, and often this observational stage allows me to back in and make changes that serve to strengthen the individual photographs as well as the series as a whole. In the image above we can see two images from a recent series I am working on, viewing these sketches together we can see how these separate images can provide context for one another. The sketches also provide hints about location, props, wardrobe, lighting, and composition. I will also write notes in the margin or additional sketches that further explain ideas that may not be obvious. For instance, in the image at the right I wasn’t convinced that the hyperbole of the man’s position inside the bush was obvious so I’ve written notes in the margin that indicate the bush should nearly be swallowing the subject.

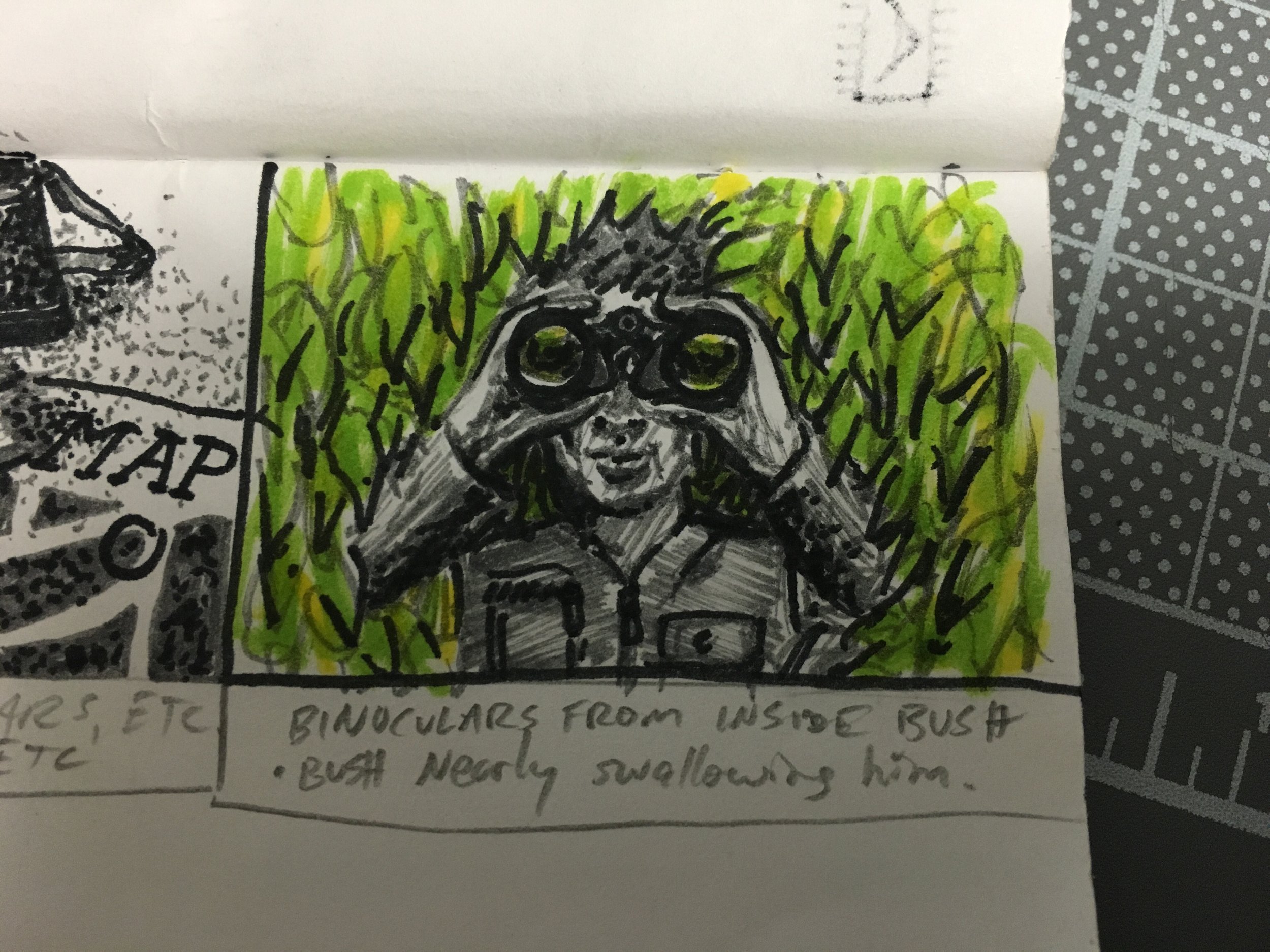

‘Observation’ Concept Sketch from the series ‘Murmurations’, 2015

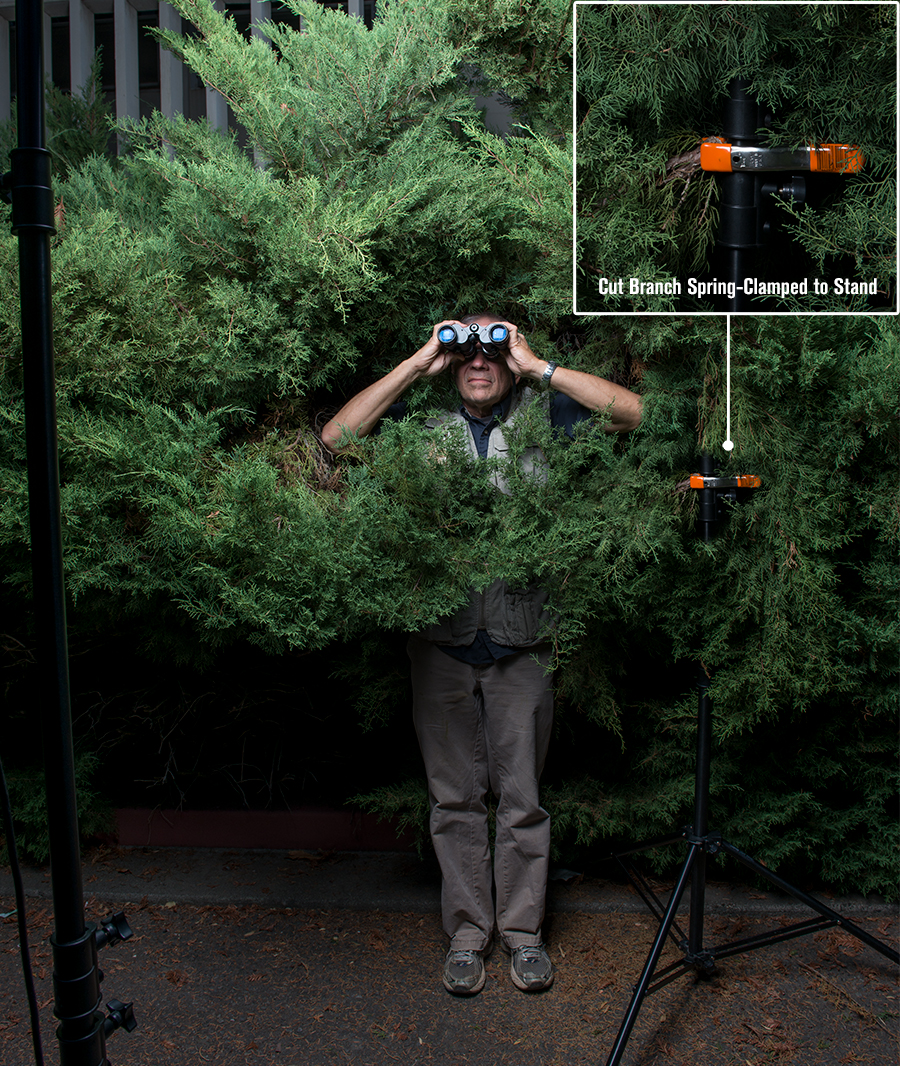

If I am happy with a sketch at this stage I will often add in a little bit of color or shadow to get an idea if my compositional strategy is still going to work once color and lighting becomes a component. Lastly, I’ll use this sketch and accompanying notes as a reference as I begin the task of location scouting, collecting/creating props and wardrobe, and as a potential reference when I start making a packing list of equipment/supplies that will be necessary to complete the shoot. This step is especially important when shooting on location. For instance if it weren’t for thoroughly sketching and outlining my ideas for this image I wouldn’t have known to pack extra stands and spring clamps as well as pruning shears in order to pull off this shot (without making my model force himself way into an extremely uncomfortable bush).

Behind the scenes of ‘Observation’, 2015

Lastly, I need to mention that when I actually show up to a shoot I almost never reference the sketch again. By the time I’m ready to shoot I’ve internalized the important components of the sketch and I need to be ready to adapt those important details to what actually ends up in front of me as I work with an actual location and the actual people and things that I need to photograph. It is only at this final step that the sketch no longer becomes a help, the preparation is finished and often I need to have my eyes wide open and be ready to evolve slightly to compensate for the unexpected curveballs that always come up, after all I am not a fortune teller and no amount of pre-visualization can ever replace the creativity and problem-solving that are an important part of actually producing an image on set/location.

I’m not breaking any new ground by spending time with paper and pen at the start of a project, it’s been an important part of pre-visualization, organization, and planning for decades in the film industry. I have found that mimicking this process has helped me be more informed about my project and my process and has consistently led to the creation of better realized and more unified photographic series.