by Kirsten Belloni

Two weeks ago I was headed home from Cambodia. I boarded the plane for the last leg of the trip feeling groggy from many hours of travel, and already fighting the 19 hour jet lag. As I got to my seat, exit row middle, I stowed my bag and made the briefest eye contact with the passenger seated next to the window. I’m shy and generally don’t talk to people on airplanes. It’s terrible I know, but I prefer a big personal space bubble and being shoulder to shoulder with a total stranger for hours is never fun.

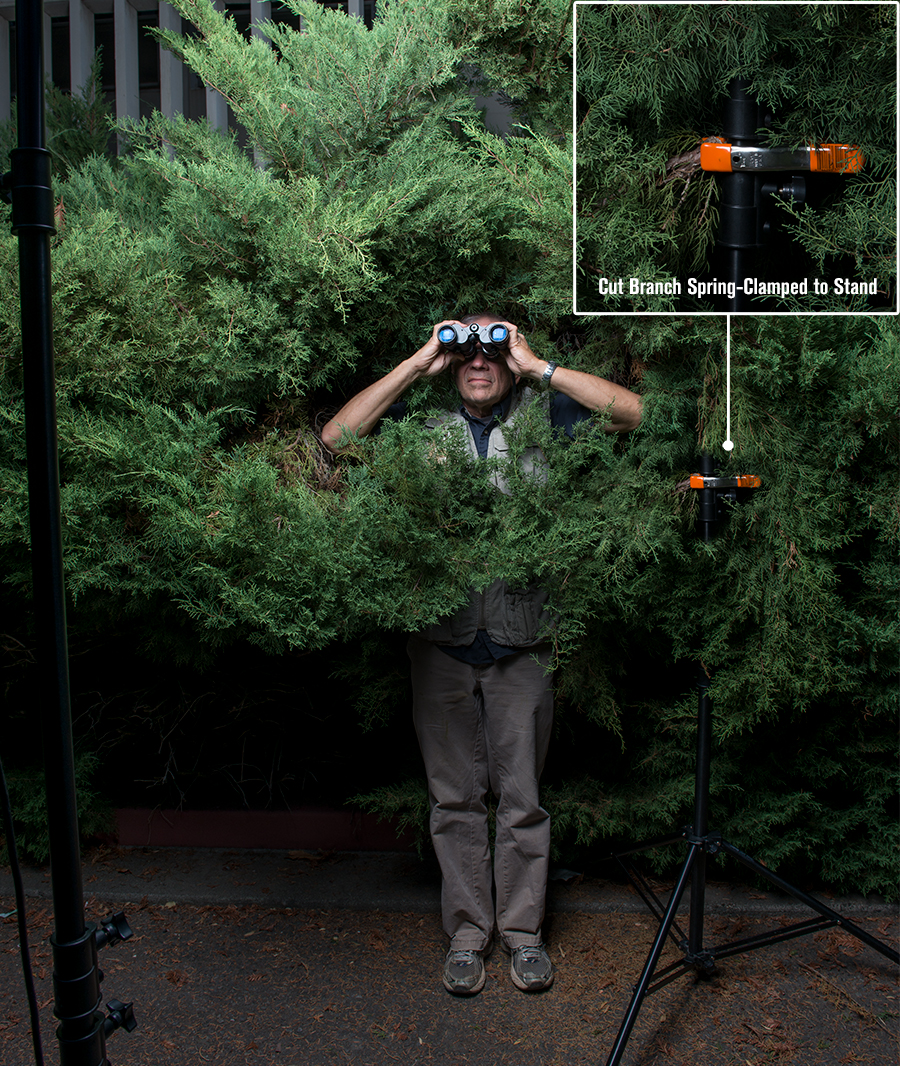

About the time that flight attendants started passing out pretzels and drinks the passenger by the window, a middle-aged man, pulled out his computer and started working on something. I glanced over out of curiosity and noticed that he was in Photoshop and editing pictures of interiors. All of a sudden my one recessive extrovert gene started to arise and I before I knew it, “Are you a photographer?” leapt from my mouth.

I was fortunate to have been seated next to Wayde Carroll, very accomplished photographer from Anchorage who specializes in commercial and editorial work. We talked for a bit and exchanged Instagram connections. I reached out to him for an interview this week. The following are his thoughts and personal experiences as a professional photographer and an Alaskan.

What led you to study photography and do you think having a formal education has helped your career? How many years have you been a professional photographer?

“I was playing music in bands in the Bay Area and working a full-time job. At 25 I realized I didn't want to end up in the career I was in and knew I couldn't count on "making it" as a musician so I decided to go back to college. My boss was very supportive and let me work any schedule I needed to keep going to school, regardless of the fact that I wasn't pursuing anything in the field of my current job. I started taking business courses because everyone said I should. I wasn't interested in that and switched my major to music. I decided I didn't want a career as a studio or symphonic musician either and switched over to an art major.

I took a photography class as an elective at San Jose State and it became obvious pretty quickly that this was the medium for me. I graduated when I was 30 and still didn't really consider a career as a photographer. It was a few years later when I stopped playing music full-time that I knew I had to do something different. My girlfriend at the time, now my wife, always wanted to teach in a Native village in Alaska. I told her that if she got a job I'd go with her. We ended up in Eek, Alaska, pop 300. It was there that I decided to start focusing on photography. It seemed like a career in which I could be creative but also possibly earn a living. It took another eight years to finally go "full-time" but it has been well worth it.

Unfortunately San Jose State had just started it's photo program when I was there so I feel my education could have been better. I learned nothing about how to actually run a business etc. That said, the school got me into photography and it changed my life. So, yes, I feel a formal education was very helpful. It was a great experience to be working with other students and be exposed to new art and new ideas as well. I think some of the really good schools would have been beneficial. That said, I learned the most by working for other photographers and making mistakes on my own.

I have been a full-time professional for 12 years now. I started relatively late! It's the best decision I ever made.”

On your website you reference leaving your "real job." What were you doing for a living prior to making photography your full time profession?

“I worked as a "precision machined parts inspector" working in the Aerospace and computer industries in the Bay Area. A job I fell into, starting at the bottom as an 18 year old with a summer job. I was also playing music regularly but you couldn't say I was making a living off of that.”

You've lived in Alaska since the early 90's. How do you think life as an Alaskan has shaped your career?

“We've lived in AK twice now. Three years the first time and going on 11 this time. We moved back up once I had worked for other photogs etc. back in California and I felt ready to go out on my own. From our first time living here I felt it would be a great place to start my business with plenty of room for new photographers. My mentor, Clark Mishler, who I worked with the first time we lived here, told me "There is always room for another good photographer". I clung to those words and decided to come back to Alaska when I was ready.

It has turned out better than expected. Being in Alaska has given me the most incredible photo opportunities. I have had commercial and editorial assignments take me all over the state. This state is filled with such amazing opportunities that are unique to our country.

Native villages,wild areas, extreme weather and lifestyles. Another mentor, Tom Bol, recommended me to lead my first photo-tour and that has changed my life as well. I now lead trips around Alaska and the world. Something I never considered. I think Alaska will continue to be an amazing place to be a photographer. With Global Warming, the oil issues, etc. there's going to be an interest up here for a long time.”

Tell me about your most epic Alaska photo shoot.

“I've done a lot of photo essays on native villages out in the bush and that's probably my favorite kind of work but my most epic assignment was a six week project I was awarded to document life on the Alaska Ferry System. I was commissioned to photograph activities on the ferry's themselves, as well as locations, history etc. at every ferry stop from Cordova down to Kodiak. It was a dream job.”

In recent years you have been leading photo tours all around the world. What led you to that?

“As I referred to above, the first time we lived here I did some assisting for Tom Bol, now a Nikon Mentor. He had been leading photo tours for Alaska Wildland Adventures (AWA). Right after I moved back to Alaska Tom called me up and said he was going to recommend me to take over for him at AWA - he was moving on to bigger things. I interviewed with AWA, got the job and my first summer back I was leading my first trip. On that trip I met the owners of Journey's International and they asked if I was interested in leading trips for them. Before I knew it I was going all over the place! An amazing and unexpected addition to my career. I really enjoy leading the trips and so far it seems people enjoy being on them. I now set up a lot of my own trips as well as still work for AWA for one trip each summer.”

We discussed Ireland briefly on the airplane, what are some of the other countries that you've done tours to and what do you look for when selecting a tour location?

“So far I have done a variety of trips in Alaska and California. Internationally I've lead trips in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Tanzania, Ireland, and Japan this coming April. I look for places that are exciting to me, places I'd like to go. Also, if I know a few people who are interested in a place I will look at designing something specifically with them in mind. I have many clients who have been on several trips with me now so sometimes we have a discussion on "where next?”. I always make sure to have local guides along who know the customs, best places for food etc., and are expert at finding wildlife. I am working on new trips to Nepal and Uganda right now.

What do you think is the biggest challenge facing professional photographers today, specifically in the genres that you specialize in (commercial, editorial, lifestyle/travel, etc).

“To me the biggest challenges are keeping up with the new ways of marketing yourself. Social media etc. Also, with the advent of digital photography there are just a ton of great photographers out there so there is a lot of competition. The younger generation really know how to give themselves strong presence on line and with social media. Keeping up with new technologies is fun but time consuming as well. You really have to wear many hats to run your own photography business.

I think there will always be a need for commercial photographers who actually know lighting, how to run a shoot, scout locations etc. There are so many great shooters capturing travel and lifestyle images that I think it will be a little tougher to make a steady income there. You see a lot of photographers doing workshops and tours now to make up for lost income in those areas, especially stock photography.”

You are the Program Chair for the American Society of Media Photographers (AK Chapter). What role do you think professional memberships play in a photography career?

“Yes, I have been the program chair for ASMP but we're having trouble keeping interest in this small community. The nature photographer's group has much more success.

That being said, Organizations such as ASMP are important. Not only do they keep you informed on current trends in photography but they invest considerable time and money into fighting for photographer's rights, especially in the realm of copyright laws etc. They also set a standard for professional business practices that are incredibly helpful when running a business on your own. It's a way to be connected to photographer's around the world.”

“Overall, being a photographer has been the most interesting and rewarding profession I can imagine. Photography has changed my life in ways I couldn't have imagined. Having a career that you love, I think, is one of the most important decisions a person can make. I'll never be rich, but I'm not trudging away waiting for retirement. I'm doing what I plan on doing until I can’t any more!

To see more of Wayde’s work:

follow him on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/waydecarroll/?hl=en

or check out his website at http://www.waydecarroll.com/