by Natalie van Sambeck

“To make art is to sing with the human voice. To do this you must first learn that the only voice you need is the voice you already have” This pearl of wisdom, which came from the book Art and Fear, reminds us that being an artist means we must speak our own truth. But what is our own truth? At its core, our own truth is intrinsically intertwined with identity, which begs the age old question “Who am I?” We tend to define this in terms of physical characteristics, social roles, and personal characteristics but is that who we really are?

According to psychologist, Bruce Hood, we only exist through a pattern of multiple influences that shape our lives. Pluck away at each influence and we cease to exist. Think of all the external influences that have touched our lives such as parents, friends, teachers, hobbies, or work. All of these aspects have made lasting impressions on us and once combined they form our whole sense of self. These impressions are created through memories and experiences, which are then strung together to create a cohesive narrative; our own personal myth.

However, our own story isn’t actually grounded in any reality. Instead, they follow a story line with our self as the star. Being the writer of our own story becomes problematic because it leaves room for an abundance of self distortions. We mold ourselves into what we think we should be, which is based by our external influences. Meanwhile, we conveniently leave out the parts that do not fit our idealized self.

What’s even more startling is that our own unique personal myths are not actually as unique as we lead ourselves to believe. Our uniqueness is actually more common ground or average in the broader spectrum. Yet we believe we are smarter, funnier, more attractive and nicer than the average person.

Don’t believe me? Take a look in the mirror. What do you see? Instantly we recognize that face as our own but we believe that this is just our external body. Deep down we believe there is more to our self. We feel it at our core. If asked where this feeling of self originates from we would all probably answer somewhere in between and above our eyes. This sensation has us believing we are unique and above average, that our body is just a vessel for the soul.

But what if that was all just an illusion perpetuated by the brain? What if we are merely reflections of our external world? This reflected self would be completely unaware that the self is an illusion simply because we can’t see that we change according to different external influences.

This is largely because we are bombarded by so much information that the brain would be overwhelmed if it had to process all of it. Instead, the brain filters through what it deems as unnecessary and keeps what it feels is important. This filtering mechanism is no different from the filtering software used in a google search. A google search engine will yield different results for different users even when they use the same keyword to search. The filtering system is based on a profile of variables relating to the specific user. In order to be able to sift through countless information, the software selects what it thinks we want to see. The brain operates in the same way only the personalization is based off external factors that influence us.

While we aren’t as different as we think we are, that doesn’t mean that we are all the same either. But we do all share a common thread that is truly undeniable. Take a look at the OCEAN approach to assessing personality traits. OCEAN stands for Openness (to try new things) , conscientiousness (self-discipline), extraversion (social interaction), agreeableness (willingness to help others), and neuroticism (self-centered worry). Otherwise called the Big Five, this approach is the most commonly accepted personality assessment in psychology. Studies reveal that our assessments change depending on the different situations or roles we assume, which supports the idea that the self is an illusion. Even more startling is that when viewed in groups, the individuals were consistent in which factors were predominate when changing roles, and thus supports that we are not as different as we think we are.

I’m sure your reading this either in complete agreement or total denial, wondering what’s the point? You thought I was talking about finding one’s voice as an artist and are now wondering how I ended up in a lengthy debate on how the brain creates a sense of self? I’ll finally get to the point. As artists we must create work that speaks our own “unique” voice and we can only do this by telling our own personal myth. The more personal we are with our artwork, the more success we have in reach a larger audience.

Suddenly our work is more relatable when we voice our own unique narrative. Why? Because we aren’t as different as we think we are. Sure we have variations in our experiences, but they are more universal than we realize. At the end of the day we are human beings that share a common thread holding us all together; the experience of existing. So create meaningful art that sings us a song with your unique voice. Speaking your own truth will inadvertently touch a larger audience on a deeper level.

Sources

[1] Hood, Bruce. The Self Illusion. How the Social Brain Creates Identity. Oxford University Press. Oxford, New York, 2102. Print.

[2] Bayles, David and Ted Orland. Art & Fear. Image Continuum. Santa Cruz, CA, 2001. Print.

by Demetrius Austin

As a photographic artist, whether commercial, Fine Art, documentary, journalist, etc, there is one area of the business that we all should be involved and aware of; copyright. Since the digital age has started, the copyright office, it’s laws, etc. have been exposed for how antiquated the technology platforms are and not keeping up with the social and technological discourse around the subject of protecting artist’s creations. “Even by the standards of the federal government, their digital operations are considered dismal and inefficient. [Forbes]”

In recent years, with the overwhelming amount of photographic data on the internet, the increasing number of photographers, increasing number of social platforms and photography contests having terms and conditions that amount to the photographer giving away all rights to their works, the copyright office has remained stagnant in their approach. In mentioning the Library of Congress above, it should be noted that the US Copyright Office currently sits under the management of the Librarian of Congress. Why does this even matter you might ask? Well, there is a new Librarian of Congress stepping into office and the head of the Copyright Office was essentially fired a little more than a week ago amid a number of different allegations stemming from performance, clashes with big tech firms like Google and the movie industry.

Either way, copyright reform is likely to happen and rather than staying away from the topic because it’s complicated is not going to help that reform. Be engaged. Be a part of organizations that have a seat at the table to lobby for copyright law that you believe in. This issue is not going away anytime soon, but yet it impacts EVERY ONE of us involved in the arts. Images below are of the new Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden and recently ousted head of the Copyright Office, Maria Pallante.

Washington Post. “Carla Hayden.” Sept 2016. Web

Fortune. “Maria Pallante.” Oct 2016. Web

by Marta Gaia Zanchi

Sharbat Gula, left on the cover of National Geographic in 1985, and then nearly two decades later, after she was featured in a story in the magazine about being reunited with the photographer. Credit: Steve McCurry/National Geographic Society, via Agence France-Presse.

Sharbat Gula was a refugee and a little girl with piercing green eyes in 1984 Afghanistan, when Steve McCurry took her photograph.

He did not know her; in fact, he did not even know her name. McCurry was walking around the Nasir Bagh camp when he heard the voices of many girls coming from a tent used as a school. Class was in progress, so he went in and started taking some images. It was not long until he saw twelve-year-old Sharbat. He was quoted to say, later in an interview: “She was curious about me as I was about her, because she had never been photographed and probably never saw a camera. After a few moments she got up and walked away.”

The image, known simply as The Afghan Girl, was published a year later and eventually became one of the most recognized photographs in the history of not just National Geographic, but of virtually any magazine. A symbol of the tragedy of Afghanistan was born. With those green eyes, all the dignity of the population of a war-ridden country shone brightest across the world. With those eyes, a little girl rose to instant recognition by millions. And with those eyes, Steve McCurry’s career as documentary photographer was launched.

There are a number of images in the history of photography that have caught the public imagination. What makes this one special, I argue though, is that it captured a minor - and was the start of a story of which she remains to this date the center of attention. Since that first meeting in 1984, National Geographic has continued to look for the girl and in 2002, found her and featured in a new article. On this occasion, the Magazine donated her a sewing machine, helped her family with some medical treatment, and funded her and her husband’s trip to Mecca on the hajj. Shortly after and inspired by this trip, National Geographic created The Afghan Girl’s Fund to provide educational opportunities for Afghan girls and young women. (The scope later broadened to include boys, and the name changed.)

Her story was brought back again to actuality last week by National Geographic, when Sharbat was arrested in Pakistan on charges of fraudulently obtaining national identity cards. Authorities said she had illegally obtained a Pakistani identity card in 1988 and a computerized identity card in 2014, while retaining her Afghan passport, which she used in 2014 to travel to Saudi Arabia for the hajj. She faces up to 14 years in prison and a fine of $3,000 to $5,000 if she is convicted.

What is in a photograph?

The story makes me pause, for many reasons. I am full of questions. Was it right to photograph a minor in full face without her parents’ permission, and catapult her to worldwide recognition? Was it right to start a decade long search for her in her adult life, prompted by the success of that one image? Does the global awareness of the tragedy of Afghanistan that this picture helped create make it right? Or, does the material support offered by the Magazine in a moment of need in her adult life make it right? Or, maybe the Fund justified the mean? And what responsibilities, if any, does National Geographic must feel now that she has been arrested? How does she feel in all this?

As a parent, I make decisions for and with my children all the time. I am struggling with one, at this very moment, which is whether to focus my MFA Thesis on my children’s photography.

So I can’t help but wonder...

What is in a photograph, for the children who are in them once they grow up?

>

<

by Brian Kyle

High school seniors find themselves at a crossroads, over the course of just a few months they are asked to make many decisions that will fundamentally alter their futures. The decisions they make at this point in their lives are arguably some of the most impactful and life-altering decisions they may make in their life. It is a time of introspection and soul searching, where they must not only identify the qualities and beliefs that make them who they are now, but also make decisions that set them on a course towards who they want to be.

These photos are portraits made of high school seniors who have found themselves thrust into this period of tumultuous introspection and decision-making.

>

<

Home Is Where The Heart Is by Natalie van Sambeck

Home is very much a state of mind. Whether we define this in terms of people, places or inanimate objects, it makes no difference. Home is our sanctuary. A place where we can go to for comfort, peace, or even solitude. We are greeted by our self every time we connect to home and it is here that we begin to get a sense for who we truly are.

My home is a sacred place nestled in the forest just off a slightly beaten path behind my family’s house. This place is where I spent most of my childhood days hunting for frogs or crayfish, building forts in trees, stomping on skunk cabbage, or looking up and counting all the stars when night began to fall. I’ve shed some tears and revealed some of my deepest secrets with these woods. It holds my hopes, my dreams, and even my fears. In essence, my self is imprinted within this place; a sacred space I call home.

>

<

Reality by Demetrius Austin

One thing that all can agree on in photography and design is the distinction of color. Each color on the wheel has a distinct color name and number assigned. We use those elements to find compliments and analogous friends among a few. However, in society, all of that logic and understanding is thrown to the wolves and where race is concerned, one of the most divisive and polarizing topics.

In this project, Reality, I explore the question of what's your reality with regard to racial discourse. Is this family truly the color black or white? What reality do you identify with and what is the rationalization behind the logic. The depictions in this mini series explore how I interpret the associations of how race is thought of in society. My desire is to slap the viewer with absurdity and force a mental reset on race categorizations. Likewise, there is a subtext of the battles a mother and father of "interracial/mixed and/or minority" kids deal with in preparing them for the world outside their control.

>

<

by Karineh Gurjian

“Researchers at the University of Kansas found that people were able to correctly judge a stranger's age, gender, income, political affiliation, emotional and other important personality traits just by looking at the person's shoes.”

We can look and examine the style, cost, color of the condition of the shoe; we can guess personal characteristics. Some things are very obvious, for example, expensive shoes belonged to high earners, flashy and colorful footwear belonged to extroverts and shoes that are not new but appeared to be spotless belonged to conscientious types.

But there are other things that we can notice, functional shoes belong to agreeable people, ankle boots fit with more aggressive personalities and uncomfortable looking shoes are worn by calm personalities.

We can also say liberal thinkers, who wear flip-flop can be considered hippies.

"Shoes convey a thin but useful slice of information about their wearers,"

As we walk down the street, we can see a variety of styles, brands, looks, and functions. So this is why I feel that they are very individual based and they carry a lot of information about the person wearing them.

>

<

I am where I live by Jody Lepinot

My home is a living being. We have a spiritual connection. There are places in my home that let me be deeply myself, where I feel especially comfortable or energized or peaceful. I’m drawn to these places every day.

In the morning I sit in my front window when I need to connect, looking out beyond my house to feel part of the neighborhood. My bathroom is a peaceful, quiet retreat. The collection of laboratory glass displayed in the window recalls happy memories of my former life. On my kitchen chest I keep the special cards Mom and I receive. I look at them and re-read them to feel my family with me. Each time I walk through my den I stop and breathe in the mystery of the window. The sheer curtains seem to float, partially concealing the personal stories told by the vases and statuettes on the sill. Windows and shelves and chests become the aediculae that give me comfort, energy and peace. They are like altars to my everyday life.

>

<

Alter Ego by Santosh Kumar Korthiwada

One has a conscious self that is more outward and meant for the rest of the world. In this photographic series I’m exploring the ‘other’ self that is more inward and more personal. That other self is nothing but an “Alter Ego”; an ego that is genuine, independent, and brutally self-critical. As human beings, we deal with many internal and external self-inflicted conflicts and contradictions; the more contradictions, the more questions arise and more we grow. Like nature, “it” changes, develops and transforms our identity in ways that are inexplicable.

This ongoing series is inspired by the words of W.E.B Dubois. He coined the term 'double consciousness' with regards to African American peoples’ identity in America...but I think the idea of double consciousness is applicable to identity in general. It is a sensation or feeling that one's identity is divided into several parts and is impossible to have a unified identity.

>

<

by Brooks Fletcher

‘Identity’ is ground by this ideas that there are facts associated with what a person or thing is. But what if those facts are vague or unclear? Can we still accurately identify the person or thing in question?

In this mini-series, To Be Identified, pedestrians and their shadows are partially captured in scenes that are composed of few visual elements. Flattened space and lines contribute to the unidentifiable nature of each scene, peaking the viewer’s interest just enough for them to question not only the identity of these people, but the characteristics of the scene itself.

Each image was created on Fujifilm Provia 100F color reversal film using a Zeiss Ikon SW Rangefinder Camera fitted with a 35mm f/2.8 lens and a 35mm optical viewfinder. This minimal, essentials-only capture process allows me to focus on discovering, dissecting, and rendering these instances into still images, but affords a level of clarity that contributes to learning more about my identity as a photographer.

In the end, these images are just as much about me and my disposition as an artist as they are the pedestrians and scenes in them.

>

<

by John Ewing

While there are certain immutable elements that form our basic self-identity, such as the physical attributes we are born with, our identities are not static. It is generally agreed that how we identify self evolves over time as we grow, learn, and experience life. Growing up, the more significant influences on our identity include familial, social, and spiritual affiliations, along with our educational experiences. As adults, our chosen vocations become a primary driver of our sense of self. In a sense, we identify ourselves based on what we do.

Since retiring from the military after twenty-seven years of service, I’ve struggled with my personal identity. In the military, my identity was closely tied to the many roles I filled. The uniform I wore was a clear signifier of both my self-identity and my identity within the military, and the community at large. Leaving that way of life behind at retirement has forced me to consciously decide how I will define my new identity. This photographic series explores the struggle of creating a new sense of self in my post-military reality using self as subject juxtaposed against a deserted landscape.

Image titles:

- Leaving the Known World Behind

- Lost

- A New Path

>

<

by Sarah Sloneker

When approaching the assignment on identity, I thought of the quote from Aristotle, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Meaning, when the individual parts are connected together to form one entity, then they are worth more than if the parts individually. For example, a “Pen” is not the ink alone, is not the cap alone, is not the tip alone … the “Pen” is the whole of the sum of all its parts.

To that idea, I am not my hands, I am not my eyes, or my feet, or my chest. My identity and soul comes from the whole of the collective, that is who I am.

by Brooks Fletcher

Did I get your attention? Good!

This NPR image is of 27-year-old Tibetan exile Janphel Yeshi. He lit himself on fire in protest of, then Chinese President, Hu Jintao’s visit to India in 2012. Yeshi was protesting against Chinese occupation of the disputed territory.

Now, there may not be a direct parallel between photography and the cultural genocide that has taken place in that region for centuries, but, figuratively speaking, photography has become art’s ‘overly’ occupied territory.

Parts I and II of this series were the manifestation of thoughts and ideas regarding the state of photography and the culture surrounding it. Each article was grounded by the idea that everyone is now a photographer. As a fellow classmate pointed out, this is a hot-button issue that might stir things up “a little bit too much.” Well, that is sort of the point.

Whether we believe it or not, the fact remains that everyone can and is taking photographs. Notice, I used the word ‘taking’ and not ‘creating.’ Unfortunately, the large majority of photographers don’t know the difference between the two, which has caused this occupation and dispute of territory.

This is a problem because most are either oblivious to this shift in the medium or are fine with it as long as their own personal and/or professional progression isn’t interrupted by it. However, this leads to a bigger problem: The ‘informed’ sitting back while the ‘uninformed’ dilute a territory rich in history and tradition. Ironically, this ‘problem’ has helped me realize that the solution will only come from doing what we truly desire.

Even as a military photojournalist, I never considered myself a professional. This made it easy for me to abandon everything I thought I knew about photography when I started this MFA program. Now that I’m here, I am more comfortable as a student than I ever was as a ‘professional.’ I find a great deal of satisfaction in bending to the will of this medium and learning more about what it is I desire. I suppose, then, my real concern is that I wish every ‘photographer’ would do the same, setting themselves ablaze in protest of those who see it otherwise and raising hell until there’s heaven.

In the next article, “The Photographic Experience, Part IV: Several Cameras Later,” I’ll assess my photographic journey up until this point and my plans for foreseeable future.

by Demetrius Austin

Like many of you, I have been working on my thesis project for a while now. I thought I was brilliant in the fact I wanted to create something personal, something that pushed me both creatively and technically and something that would benefit me professionally as well since I am actively doing commercial work. From the start of the project I pursued technically complicated imagery with subjects that looked great on the camera and of course were great

physical specimens. The final creations demonstrated a pretty decent control of lighting,creativity and Photoshop prowess. The subjects were relatable and passionate about being healthy.

Austin, Demetrius. “Technical Analyst”. July 2015

From cycling, working out in the snow and rain, the project was moving forward even though there were hiccups. I was even able to successfully sell the idea of the project a lot easier with a more refined abstract, sample images that had been reviewed by both faculty and my peers and an end game I believed had the depth necessary to move forward both academically and professionally. Until October 2015, I could and would have continued moving forward with that trajectory and ultimately happy. However, the life of this project became a bit more life altering. Meet Dustin, a man with a very fascinating story along with a passion for being a professional athlete that is unquestionable and made me look at this project in a different light.

Austin, Demetrius. “Dustin S.” October 2015.

At the age of 17, Dustin was a star football player with a full life ahead and likely looking at a few scholarships to play at a top level college. In an instant, everything changed. He was in a car accident that placed him on a surgical table where he died twice. Afterwards, he had to learn how to do everything over again, to include walking. His motivation was and is to defy the odds and not only learn to walk, but to live life with no limitations. Dustin went on to finish college, play in the arena football league, fight in the MMA all while working in highway construction for his parent’s company. Dustin’s story has heightened my pursuit to find people that not only have a passion for their sport and/or health, but have had life altering experiences in order to operate at the level they do today.

by John Ewing

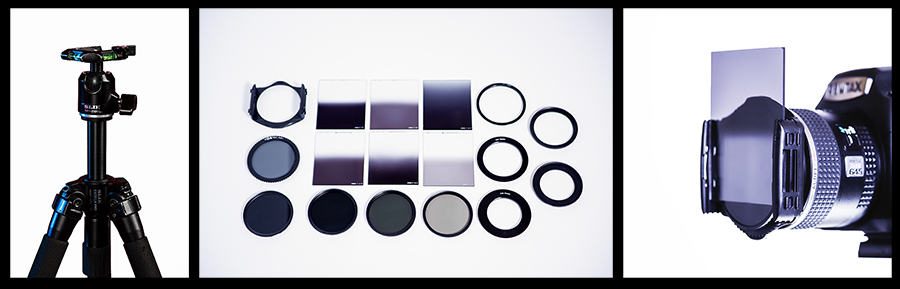

In the last installment I discussed tracking the weather and the methods I used to pick locations for my storm-driven landscape images. This week, I wanted to start the discussion of capture techniques by talking about some of the basic tools that I use in creating my landscape work. While some of the tools I describe can be emulated in post-processing, it is always preferable to get the initial capture as close as possible to the intended final print statement in-camera. The less pixel manipulation in post-processing, the higher the quality of the final product. I use the following tools regularly to help create the strongest initial capture possible, and feel they have a place in most landscape photographers’ kit.

Tripod, Tripod Head & Tripod Weight

I use my tripod on every landscape image that I shoot for two primary reasons. First and most obvious is that when I need to use slow shutter speeds, such as in low light conditions, or if I’m wanting to capture motion, the tripod keeps the camera steady. The other not so obvious reason is that it helps me to slow down and more carefully consider my composition.

When choosing a tripod, it is important to consider both the maximum working height and weight limits to ensure they meet your requirements. It is also important to consider the type of tripod head you want to work with. I prefer a ball head, as seen below, but the important thing is to use what you are most comfortable with. One additional accessory to consider when looking for a tripod is a hook or loop that you can attach a weight to. My tripod has a loop underneath that I hang my camera bag from to dampen wind-induced camera shake. If you expect to shoot in windy conditions, consider adding the capability to weigh down your tripod, but make sure that you don’t exceed your tripod’s working weight limit.

Camera Level

Fixing your horizon line is fairly simple to accomplish in post-processing, but getting it right in-camera leaves one less adjustment you’ll need to accomplish in post-processing. Many newer cameras now have electronic levels built into the viewfinder and/or the camera’s display screen. These levels provide feedback on both the horizontal axis and the forward/backward tilt axis. Simply pull up the level display, loosen the head, then move the camera into a level attitude using the visual prompts. Tighten the head and you are good to go. In the event that your camera doesn’t have the electronic level, you can attach a spirit level, also known as a bubble level, to your camera’s hot shoe and get the same results. The image below shows examples of Canon and Pentax electronic levels, as well as a spirit level.

John Ewing, Tripod, Filter Set, Filter Holder on Camera, 16 October 2016.

Filter Kit

Where your tripods and camera level are functional tools that help get the camera set up to shoot, filters provide flexibility in controlling light beyond shutter speed, exposure and ISO. Ultimately, they provide the basic creative building blocks for making the final image. As a brief refresher, human eyes have a functional dynamic range estimated to exceed 24 f-stops. While we can’t correlate this precisely to a camera’s static dynamic range, DSLRs frequently have a dynamic range of 8-11 f-stops, our eyes can still perceive and appreciate large differences in value that a camera simply can’t match. Use of specific filters can compress the range of values across an image to keep details in the shadows without blowing out the highlights, such as when shooting a bright sky and much darker foreground. I frequently use filters to achieve a low- to mid-value contrast across an image. To accomplish this, I carry a circular polarizing filter, a set of neutral density filters, and a set of graduated neutral density filters, as well as the associated holders and adapters.

Polarizing Filters

Polarizing filters are primarily intended to decrease or eliminate reflections and glare from the surface of shiny objects. This is especially useful in taking the reflective sheen off of water elements and giving it a darker appearance. As an added bonus for the landscape photographer, they also add contrast and saturate colors to a degree. I use a polarizer primarily for the way it creates depth in the clouds through the added contrast and saturation. With clear skies however, and especially with wide angle lenses, it is important to be mindful of your angle to the sun or you are likely to end up with a dark vignette or an uneven color gradation across your sky (polarizers work best when you are shooting with the sun at 90 degrees from the image plane). Also, there is a difference between polarizers used for digital work and those used with film. If you are shooting digital, ensure you get a polarizer that is made for digital cameras.

Neutral Density (ND) Filters

The primary function of the ND filter is to decrease the amount of light hitting your sensor or film. Because they filter the full spectrum of light waves, they do not affect color rendering. They are available in a range of densities, and always require adjustments in aperture and/or shutter speed. The densities are generally measured based on the f-stop reduction the filter provides (e.g. the set I use includes four filters rated at -1, -2, -3, and -4 f-stops). If I’m in a situation where I can’t use a polarizing filter and need to decrease the value across the entire image, I’ll use a standard ND filter. As a result, my shutter speeds are longer to compensate. NDs are also perfect for controlling exposure while capturing motion (i.e. for waterfalls, streams, etc.).

Graduated Neutral Density

Graduated ND filters are without a doubt the workhorses of my filter kit, and can be used to functionally compress the dynamic range of an image. Graduated ND filters transition from clear at one end to dark at the other. Like the standard ND filters, Graduated ND filter ratings are based on the f-stop reduction of each filter, as well as how quickly the filter transitions from clear to dark. They also come in a wide assortment of densities and transitions to meet virtually any requirement (see below for an assortment of ND and Graduated ND filters). While there are circular, screw-in Graduated ND filters, I prefer to use rectangular “drop-in” filters using a dedicated filter holder.

As I mentioned above, these filters are my workhorses and it is rare for me to capture a landscape image without one. Frequently, it is the value difference between the sky and ground elements that exceed a camera’s dynamic range and using one or more Graduated ND filter can bring highlights down to a manageable level. Generally, the dark portion of the filter is used to cover the sky, with the transition line (when present) being aligned with the horizon line. In some situations, such as sun reflecting off of water or snow, the dense part of the filter will be reversed to bring down the value of the foreground. As with standard ND filters, Graduated NDs can be stacked to some degree. It isn’t unusual for me to have a Polarizing filter, a standard ND filter and a Graduated ND filter in place for a shoot.

Camera Levels (Canon 5D Mark III, Spirit Level, Pentax 645Z), 16 October 2016

Filter Holder & Adapter Rings

The last portion of the filter kit includes the rings, holders and adapters that allow you to use the tools we’ve covered. There are many manufactures and styles of filters, each with their own mounting hardware, so I’d recommend taking a look at what is available. My kit is set up so I can use one set of filters on all of my lenses by using adapters. For my circular polarizer and Graduated ND filters, I use the Cokin P-Series filters and holder. The holder mounts onto an adapter ring, the polarizer drops into the first slot, and Graduated ND filters load in the second and third slots. (see above for an image of the filter holder on my camera with polarizer and Gradated ND filter). I have rings for each of my lenses so I can pull the holder off and reattach if I change lenses. My standard ND filters are screw-on and work with my largest diameter lens, and I have step-down adapters for each smaller lens. In the event that I need to use a polarizer and/or Graduated ND filter with a standard ND filter, I can put the Cokin adapter ring directly onto the standard ND filter and hang the Cokin holder there.

While this filter set-up may seem a little confusing at first, taking some time to experiment with each of them, as well as stacking them, you’ll quickly develop a feel for the flexibility they provide in allowing you to control the light for your own creative purposes.

Sources

“Cameras VS. The Human Eye.” Cambridge in Color. 2016. Web http://www.cambridgeincolour.com/tutorials/cameras-vs-human-eye.ht

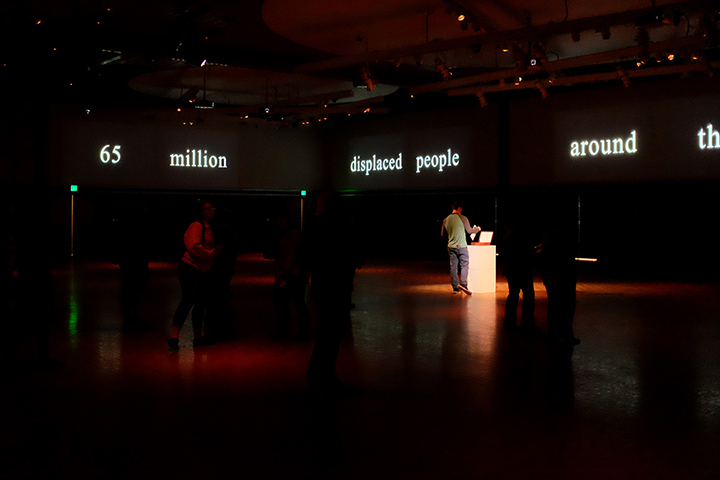

![Image: Mark David [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ccfc39e4b0ff38cd532d8c/1487632266414-D8QZYHZMVLOTPOQ5FQM3/image-asset.jpeg)

![Image: Reuters. [6]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ccfc39e4b0ff38cd532d8c/1487632400003-UM2QM6V0F8LMF2EHJRTE/image-asset.jpeg)

![Prints on prints on print. Credit: Matt Titone [8]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55ccfc39e4b0ff38cd532d8c/1487632482734-BNPKDATF6DPVBP64UEWB/image-asset.jpeg)